‘This Is Water’ by David Foster Wallace

David Foster Wallace

There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish

swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys, how’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

If you’re worried that I plan to present myself here as the wise old fish explaining what water is, please don’t be. I am not the wise old fish. The immediate point of the fish story is that the most obvious, ubiquitous, important realities are often the ones that are the hardest to see and talk about.

Stated as an English sentence, of course, this is just a banal platitude – but the fact is that, in the day-to-day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have life-or-death importance. That may sound like hyperbole, or abstract nonsense. So let’s get concrete … A huge percentage of the stuff that I tend to be automatically certain of is, it turns out, totally wrong and deluded.

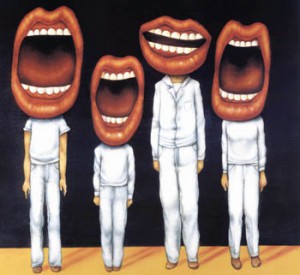

Here’s one example of the utter wrongness of something I tend to be automatically sure of: everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute centre of the universe, the realest, most vivid and important person in existence. We rarely talk about this sort of natural, basic self-centredness, because it’s so socially repulsive, but it’s pretty much the same for all of us, deep down. It is our default setting, hard-wired into our boards at birth.

Think about it: there is no experience you’ve had that you were not at the absolute centre of. The world as you experience it is right there in front of you, or behind you, to the left or right of you, on your TV, or your monitor, or whatever. Other people’s thoughts and feelings have to be communicated to you somehow, but your own are so immediate, urgent, real – you get the idea.

But please don’t worry that I’m getting ready to preach to you about compassion or other-directedness or the so-called “virtues”. This is not a matter of virtue – it’s a matter of my choosing to do the work of somehow altering or getting free of my natural, hard-wired default setting, which is to be deeply and literally self-centred, and to see and interpret everything through this lens of self.

By way of example, let’s say it’s an average day, and you get up in the morning, go to your challenging job, and you work hard for nine or ten hours, and at the end of the day you’re tired, and you’re stressed out, and all you want is to go home and have a good supper and maybe unwind for a couple of hours and then hit the rack early because you have to get up the next day and do it all again.

But then you remember there’s no food at home – you haven’t had time to shop this week, because of your challenging job – and so now, after work, you have to get in your car and drive to the supermarket. It’s the end of the workday, and the traffic’s very bad, so getting to the store takes way longer than it should, and when you finally get there the supermarket is very crowded, because of course it’s the time of day when all the other people with jobs also try to squeeze in some grocery shopping, and the store’s hideously, fluorescently lit, and infused with soul-killing Muzak or corporate pop, and it’s pretty much the last place you want to be, but you can’t just get in and quickly out: you have to wander all over the huge, overlit store’s crowded aisles to find the stuff you want, and you have to manoeuvre your junky cart through all these other tired, hurried people with carts, and of course there are also the glacially slow old people and the spacey people and the kids who all block the aisle and you have to grit your teeth and try to be polite as you ask them to let you by, and eventually, finally, you get all your supper supplies, except now it turns out there aren’t enough checkout lanes open even though it’s the end-of-the-day rush, so the checkout line is incredibly long, which is stupid and infuriating, but you can’t take your fury out on the frantic lady working the register.

Anyway, you finally get to the checkout line’s front, and pay for your food, and wait to get your cheque or card authenticated by a machine, and then get told to “Have a nice day” in a voice that is the absolute voice of death, and then you have to take your creepy flimsy plastic bags of groceries in your cart through the crowded, bumpy, littery parking lot, and try to load the bags in your car in such a way that everything doesn’t fall out of the bags and roll around in the trunk on the way home, and then you have to drive all the way home through slow, heavy, SUV-intensive rush-hour traffic, etc, etc.

The point is that petty, frustrating crap like this is exactly where the work of choosing comes in. Because the traffic jams and crowded aisles and long checkout lines give me time to think, and if I don’t make a conscious decision about how to think and what to pay attention to, I’m going to be pissed and miserable every time I have to food-shop, because my natural default setting is the certainty that situations like this are really all about me, about my hungriness and my fatigue and my desire to just get home, and it’s going to seem, for all the world, like everybody else is just in my way, and who are all these people in my way? And look at how repulsive most of them are and how stupid and cow-like and dead-eyed and nonhuman they seem here in the checkout line, or at how annoying and rude it is that people are talking loudly on cell phones in the middle of the line, and look at how deeply unfair this is: I’ve worked really hard all day and I’m starved and tired and I can’t even get home to eat and unwind because of all these stupid goddamn people.

Or if I’m in a more socially conscious form of my default setting, I can spend time in the end-of-the-day traffic jam being angry and disgusted at all the huge, stupid, lane-blocking SUVs and Hummers and V12 pickup trucks burning their wasteful, selfish, 40-gallon tanks of gas, and I can dwell on the fact that the patriotic or religious bumper stickers always seem to be on the biggest, most disgustingly selfish vehicles driven by the ugliest, most inconsiderate and aggressive drivers, who are usually talking on cell phones as they cut people off in order to get just 20 stupid feet ahead in a traffic jam, and I can think about how our children’s children will despise us for wasting all the future’s fuel and probably screwing up the climate, and how spoiled and stupid and disgusting we all are, and how it all just sucks …

If I choose to think this way, fine, lots of us do – except that thinking this way tends to be so easy and automatic it doesn’t have to be a choice. Thinking this way is my natural default setting. It’s the automatic, unconscious way that I experience the boring, frustrating, crowded parts of adult life when I’m operating on the automatic, unconscious belief that I am the centre of the world and that my immediate needs and feelings are what should determine the world’s priorities.

The thing is that there are obviously different ways to think about these kinds of situations. In this traffic, all these vehicles stuck and idling in my way: it’s not impossible that some of these people in SUVs have been in horrible car accidents in the past and now find driving so traumatic that their therapist has all but ordered them to get a huge, heavy SUV so they can feel safe enough to drive; or that the Hummer that just cut me off is maybe being driven by a father whose little child is hurt or sick in the seat next to him, and he’s trying to rush to the hospital, and he’s in a much bigger, more legitimate hurry than I am – it is actually I who am in his way.

Again, please don’t think that I’m giving you moral advice, or that I’m saying you’re “supposed to” think this way, or that anyone expects you to just automatically do it, because it’s hard, it takes will and mental effort, and if you’re like me, some days you won’t be able to do it, or you just flat-out won’t want to.

But most days, if you’re aware enough to give yourself a choice, you can choose to look differently at this fat, dead-eyed, over-made-up lady who just screamed at her little child in the checkout line – maybe she’s not usually like this; maybe she’s been up three straight nights holding the hand of her husband who’s dying of bone cancer, or maybe this very lady is the low-wage clerk at the Motor Vehicles Dept who just yesterday helped your spouse resolve a nightmarish red-tape problem through some small act of bureaucratic kindness.

Of course, none of this is likely, but it’s also not impossible – it just depends on what you want to consider.

If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is and who and what is really important – if you want to operate on your default setting – then you, like me, will not consider possibilities that aren’t pointless and annoying.

But if you’ve really learned how to think, how to pay attention, then you will know you have other options. It will be within your power to experience a crowded, loud, slow, consumer-hell-type situation as not only meaningful but sacred, on fire with the same force that lit the stars – compassion, love, the sub-surface unity of all things.

Not that that mystical stuff’s necessarily true: the only thing that’s capital-T True is that you get to decide how you’re going to try to see it. You get to consciously decide what has meaning and what doesn’t. You get to decide what to worship.

Because here’s something else that’s true. In the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And an outstanding reason for choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship – be it JC or Allah, be it Yahweh or the Wiccan mother-goddess or the Four Noble Truths or some infrangible set of ethical principles – is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive.

If you worship money and things – if they are where you tap real meaning in life – then you will never have enough. Never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your own body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly, and when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally plant you.

On one level, we all know this stuff already – it’s been codified as myths, proverbs, clichés, bromides, epigrams, parables: the skeleton of every great story. The trick is keeping the truth up front in daily consciousness.

Worship power – you will feel weak and afraid, and you will need ever more power over others to keep the fear at bay. Worship your intellect, being seen as smart – you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out.

The insidious thing about these forms of worship is not that they’re evil or sinful; it is that they are unconscious. They are default settings. They’re the kind of worship you just gradually slip into, day after day, getting more and more selective about what you see and how you measure value without ever being fully aware that that’s what you’re doing.

And the world will not discourage you from operating on your default settings, because the world of men and money and power hums along quite nicely on the fuel of fear and contempt and frustration and craving and the worship of self. Our own present culture has harnessed these forces in ways that have yielded extraordinary wealth and comfort and personal freedom. The freedom to be lords of our own tiny skull-sized kingdoms, alone at the centre of all creation.

This kind of freedom has much to recommend it. But there are all different kinds of freedom, and the kind that is most precious you will not hear much talked about in the great outside world of winning and achieving and displaying.

The really important kind of freedom involves attention, and awareness, and discipline, and effort, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them, over and over, in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day. That is real freedom. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default setting, the “rat race” – the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing. I

know that this stuff probably doesn’t sound fun and breezy or grandly inspirational. What it is, so far as I can see, is the truth with a whole lot of rhetorical bullshit pared away. Obviously, you can think of it whatever you wish. But please don’t dismiss it as some finger-wagging Dr Laura sermon.

None of this is about morality, or religion, or dogma, or big fancy questions of life after death. The capital-T Truth is about life before death. It is about making it to 30, or maybe 50, without wanting to shoot yourself in the head.

It is about simple awareness – awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, that we have to keep reminding ourselves, over and over: “This is water, this is water.”

· Adapted from the commencement speech the author gave to a graduating class at Kenyon College, Ohio

This version is taken from the Guardian website, where it is bizarrely described as ‘fiction’. It is also published in book form by Hachette.

Since the development of scanners that can measure blood flow in the brain without seriously harming people, we have been learning a lot about how our brains work. Some journalists have called this the

Since the development of scanners that can measure blood flow in the brain without seriously harming people, we have been learning a lot about how our brains work. Some journalists have called this the