You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘psychology’ category.

Human beings evolved as much prey as predators. To survive, our ancestors had to be hyper-vigilant for threat – you only have to miss the sabre-toothed tiger in the grass once for your genes to leave the gene pool.* So, we have evolved to be constantly on the lookout for threats – that’s handy when you’re crossing the road, but most of the time we’re not really in that much danger. Unfortunately the unconscious processes of your mind don’t know that, so they react to minor criticisms, disagreements and mistakes as though they are threats to your very existence.

This is known as the Negativity Bias – neuropsychologist Rick Hanson describes our minds as having evolved to be ‘teflon for positivity, but velcro for negativity’. I’m sure you’re familiar with the experience of receiving feedback, and managing to pretty much ignore all of the appreciations, while focusing your attention sharply on the one thing that isn’t enthusiastically appreciative. All of which makes life pretty unpleasant at times – that’s because evolution doesn’t care whether you are happy or not, all it’s worried about is that you pass on your genes.**

Fortunately neuroplasticity allows us to reprogram our brains so that instead of constantly looking out for failure, rejection and threat we learn to look out for success, acceptance and possibility. This is the principle of Solution Focus approaches.

In a simple machine, knowing what the problem is can be a real help – you just replace the broken part and everything is sorted. In a complex system like the human psyche, a business or a community, learning all you can about a problem may make you an expert on problems, but usually won’t tell you very much that’s useful about the solution.

Solution Focused inquiries, like ‘when doesn’t the problem occur?’ or ‘where do things work best?’ bring a different perspective to situations, and start to open up possibilities. They also help the brain to work in a way that stimulates creativity, rather than triggering defensive fight/flight responses.

Learning to rewire the way you approach life isn’t an overnight job – after all you’re working against millions of years of evolution – but you can experience positive effects very quickly. Here’s a little exercise I almost always give to my coaching clients, and regularly do myself.

Give yourself 10 minutes and write a list of What’s working?/What’s better? make the list as long as you possibly can and include as wide a range of things as possible – from the cup of tea that you just enjoyed, to a major work achievement, to someone opening the door for you, anything and everything you can think of – keep asking yourself ‘and what else?’.

You can do this on your phone, tablet or computer, and it works even better if you use pen and paper. Once you’ve finished your Working/Better list you can write your To Do list – make sure all the items on that list are small and specific first steps ‘send an email to Bob to arrange a meeting’ rather than ‘renegotiate the Bob Co. contract’.

What this does is gets your brain firing on all the networks associated with success, connection, and positivity, so you feel well resourced to tackle the jobs ahead – and breaking those jobs down into bite-size chunks helps to avoid the tendency to get overwhelmed. And it sometimes helps you to notice opportunities that you might otherwise overlook.

Give it a try, all you’ve got to lose is your negativity bias.

* Disclaimer – I have no idea whether sabre toothed tigers did actually hunt hominids, but you get the point

** Disclaimer 2 – Evolution is a process, to describe it as caring or not caring about something is ludicrous – but you get the point.

Since the development of scanners that can measure blood flow in the brain without seriously harming people, we have been learning a lot about how our brains work. Some journalists have called this the Golden Age of Neuroscience, although it’s more likely to turn out to be the Dawn of Neuroscience. We’re learning that the human brain is far more extraordinary than we ever thought – as far as we know, it is the most complex thing in the universe.

Since the development of scanners that can measure blood flow in the brain without seriously harming people, we have been learning a lot about how our brains work. Some journalists have called this the Golden Age of Neuroscience, although it’s more likely to turn out to be the Dawn of Neuroscience. We’re learning that the human brain is far more extraordinary than we ever thought – as far as we know, it is the most complex thing in the universe.

One of the things we have learnt is that the brain is in a constant process of change: everything we do, think and say subtly alters the network of neurones in the brain, a process described as neuroplasticity. Any given behaviour – let’s say being frightened by a dog – strengthens the connections of a particular sequence of neurones, creating what is called a neural-network. If we repeat the behaviour, then that particular neural network is reinforced – as neuroscientist Donald Hebb put it (back in 1949!) “what fires together, wires together“.

What this means is that every time you repeat a behaviour, you gradually wire up your brain in a way that makes that way of responding to events more likely, and ultimately so habitual that it takes great effort for you to choose another way of responding. So an incident of being frightened by a dog can be reinforced again and again, so that being frightened of dogs in general becomes a deeply ingrained habit.

Of course the early practitioners of Buddhism had no idea what was happening in the brain, but through seeing people’s behaviour and watching their own minds in very subtle detail in meditation, they were able to observe the way in which we gradually build, embed and reinforce our habits of relating to the world. They called this process karma.

Over time, of course, the meaning and interpretation of words drifts. Nowadays people tend to talk of karma as some kind of cosmic retribution system – it is even embedded in the Hindu caste system: if you are born in a lowly caste, then this is your karma for having been bad in your previous life – and some people have even applied this absurd reasoning to disabled people.

Sadly, some cruel and exploitative people are never punished; some kind and generous people live lives of great difficulty and distress. Your karma is your mind – your particular set of reactive habits to the world and your experiences: feeling threatened by people in authority, or the psychologically damaged person on public transport; getting angry (or collapsing) when people disagree with your opinions; whether you like or are frightened of dogs.

Karma was not, and is not, a description of a great cosmic process, but an incredibly sophisticated way for a pre-scientific society to make sense of the development of neural-networks in the brain. And the fantastic thing is, it’s never too late for you to create new neural-networks that are more helpful, more kind, more creative, and happier. John Lennon was wrong, Instant Karma isn’t necessarily gonna get you.

1 Give yourself permission to feel whatever you feel

However inappropriate or unworthy it might seem let it arise and pass away, resisting the temptation to attach great significance to it.

Grief is non-linear – one day you might feel fantastic, and the next furious, and the next exhausted, and so it will go on.

When you are bereaved, whether by a death or another kind of ending in your life, it is as though part of your soul moves into the underworld. The time-scales of the underworld are very slow, and care nothing for the efficient productivity of the bright light of day. For most of us this is massively inconvenient, as we need to get on with work, family life, etc, but we just have to let it work its way through at its own rate. Be kind and patient with yourself – it might well take longer than you think it should or want it to.

What would you suggest to help someone who has been bereaved?

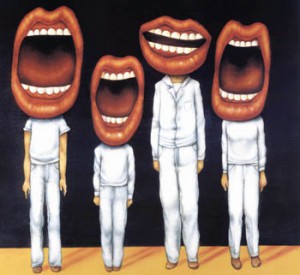

- Tell the truth – Resist the temptation to exaggerate or understate for effect or to emphasise a point. Be as factually accurate as possible – without boring the pants of people!

- Be kind – This may be more important in your internal communication than your communication with others. Either way, avoid the temptation to use the truth as a weapon, and avoid harshness – both in tone and in content.

- Create harmony – Resist getting caught up in gossiping and avoid slagging people off. Speak appreciatively of others as often as you can, and break the habit of internal moaning.

- Make sure what you say is worth hearing – Talk about the things in life that are genuinely significant – go beyond property prices, technological gadgets and celebrity gossip so that you use communication as a way of genuinely connecting with yourself and other people.

- Is now the right time? – It might have been preying on your mind all day, but is it really ideal to pounce on somebody as soon as they’ve come through the door? Take the other person into account before you launch into explaining your solution to the economic crisis.

- Take responsibility for understanding – If you don’t understand what someone has said, apologise for not getting it and ask them to explain it again (rather than blaming them for not explaining it properly). Check that you have been understood – if you haven’t, then apologise for not being clear enough and explain it again.

- Seek first to understand, then to be understood – This is a bit of a hoary old chestnut, but none the less helpful for that. What’s it like when someone insists on thrusting their opinion down your throat? It’s likely to make you gag, so don’t do it to others.

- Saying the same thing louder is unlikely to aid understanding. This was the comedy hub for dozens of ‘Brits abroad’ sitcom based movies in the 70s – it wasn’t very funny then, and it still doesn’t work. If what you’re saying isnlt understood you need to find a new way of getting the point across.

- It’s OK for others to disagree – If someone disagrees with us we normally think that they don’t understand, then we think they’re stupid, then we think they’re evil. Actually, they probably just disagree – and that’s fine.

- Have periods of silence – Allow some space in your head, and some quietness in the world. Learn to be with others on companionable silence – at least once in a while.

This is a famous piece from the Gestalt tradition, which I think is very important.

The Paradoxical Theory of Change

For nearly a half century, the major part of his professional life, Frederick Perls was in conflict with the psychiatric and psychological establishments. He worked uncompromisingly in his own direction, which often involved fights with representatives of more conventional views. In the past few years, however, Perls and his Gestalt therapy have come to find harmony with an increasingly large segment of mental health theory and professional practice. The change that has taken place is not because Perls has modified his position, although his work has undergone some transformation, but because the trends and concepts of the field have moved closer to him and his work.

Perls’s own conflict with the existing order contains the seeds of his change theory. He did not explicitly delineate this change theory, but it underlies much of his work and is implied in the practice of Gestalt techniques. I will call it the paradoxical theory of change, for reasons that shall become obvious. Briefly stated, it is this: that change occurs when one becomes what he is, not when he tries to become what he is not. Change does not take place through a coercive attempt by the individual or by another person to change him, but it does take place if one takes the time and effort to be what he is — to be fully invested in his current positions. By rejecting the role of change agent, we make meaningful and orderly change possible.

The Gestalt therapist rejects the role of “changer,” for his strategy is to encourage, even insist, that the patient be where and what he is. He believes change does not take place by “trying,” coercion, or persuasion, or by insight, interpretation, or any other such means. Rather, change can occur when the patient abandons, at least for the moment, what he would like to become and attempts to be what he is. The premise is that one must stand in one place in order to have firm footing to move and that it is difficult or impossible to move without that footing.

The person seeking change by coming to therapy is in conflict with at least two warring intrapsychic factions. He is constantly moving between what he “should be” and what he thinks he “is,” never fully identifying with either. The Gestalt therapist asks the person to invest himself fully in his roles, one at a time. Whichever role he begins with, the patient soon shifts to another. The Gestalt therapist asks simply that he be what he is at the moment.

The patient comes to the therapist because he wishes to be changed. Many therapies accept this as a legitimate objective and set out through various means to try to change him, establishing what Perls calls the “topdog/under-dog” dichotomy. A therapist who seeks to help a patient has left the egalitarian position and become the knowing expert, with the patient playing the helpless person, yet his goal is that he and the patient should become equals. The Gestalt therapist believes that the topdog/under-dog dichotomy already exists within the patient, with one part trying to change the other, and that the therapist must avoid becoming locked into one of these roles. He tries to avoid this trap by encouraging the patient to accept both of them, one at a time, as his own.

The analytic therapist, by contrast, uses devices such as dreams, free associations, transference, and interpretation to achieve insight that, in turn, may lead to change. The behaviorist therapist rewards or punishes behavior in order to modify it. The Gestalt therapist believes in encouraging the patient to enter and become whatever he is experiencing at the moment. He believes with Proust, “To heal a suffering one must experience it to the full.”

The Gestalt therapist further believes that the natural state of man is as a single, whole being — not fragmented into two or more opposing parts. In the natural state, there is constant change based on the dynamic transaction between the self and the environment.

Kardiner has observed that in developing his structural theory of defense mechanisms, Freud changed processes into structures (for example, denying into denial). The Gestalt therapist views change as a possibility when the reverse occurs, that is, when structures are transformed into processes. When this occurs, one is open to participant interchange with his environment.

If alienated, fragmentary selves in an individual take on separate, compartmentalized roles, the Gestalt therapist encourages communication between the roles; he may actually ask them to talk to one another. If the patient objects to this or indicates a block, the therapist asks him simply to invest himself fully in the objection or the block. Experience has shown that when the patient identifies with the alienated fragments, integration does occur. Thus, by being what one is–fully–one can become something else.

The therapist, himself, is one who does not seek change, but seeks only to be who he is. The patient’s efforts to fit the therapist into one of his own stereotypes of people, such as a helper or a top-dog, create conflict between them. The end point is reached when each can be himself while still maintaining intimate contact with the other. The therapist, too, is moved to change as he seeks to be himself with another person. This kind of mutual interaction leads to the possibility that a therapist may be most effective when he changes most, for when he is open to change, he will likely have his greatest impact on his patient.

What has happened in the past fifty years to make this change theory, implicit in Perls’s work, acceptable, current, and valuable? Perls’s assumptions have not changed, but society has. For the first time in the history of mankind, man finds himself in a position where, rather than needing to adapt himself to an existing order, he must be able to adapt himself to a series of changing orders. For the first time in the history of mankind, the length of the individual life span is greater than the length of time necessary for major social and cultural change to take place. Moreover, the rapidity with which this change occurs is accelerating.

Those therapies that direct themselves to the past and to individual history do so under the assumption that if an individual once resolves the issues around a traumatic personal event (usually in infancy or childhood), he will be prepared for all time to deal with the world; for the world is considered a stable order. Today, however, the problem becomes one of discerning where one stands in relationship to a shifting society. Confronted with a pluralistic, multifaceted, changing system, the individual is left to his own devices to find stability. He must do this through an approach that allows him to move dynamically and flexibly with the times while still maintaining some central gyroscope to guide him. He can no longer do this with ideologies, which become obsolete, but must do it with a change theory, whether explicit or implicit. The goal of therapy becomes not so much to develop a good, fixed character but to be able to move with the times while retaining some individual stability.

In addition to social change, which has brought contemporary needs into line with his change theory, Perls’s own stubbornness and unwillingness to be what he was not allowed him to be ready for society when it was ready for him. Perls had to be what he was despite, or perhaps even because of, opposition from society. However, in his own lifetime he has become integrated with many of the professional forces in his field in the same way that the individual may become integrated with alienated parts of himself through effective therapy.

The field of concern in psychiatry has now expanded beyond the individual as it has become apparent that the most crucial issue before us is the development of a society that supports the individual in his individuality. I believe that the same change theory outlined here is also applicable to social systems, that orderly change within social systems is in the direction of integration and holism; further, that the social-change agent has as his major function to ‘work with and in an organization so that it can change consistently with the changing dynamic equilibrium both within and outside the organization. This requires that the system become conscious of alienated fragments within and without so it can bring them into the main functional activities by processes similar to identification in the individual. First, there is an awareness within the system that an alienated fragment exists; next that fragment is accepted as a legitimate outgrowth of a functional need that is then explicitly and deliberately mobilized and given power to operate as an explicit force. This, in turn. leads to communication with other subsystems and facilitates an integrated, harmonious development of the whole system.

With change accelerating at an exponential pace, it is crucial for the survival of mankind that an orderly method of social change be found. The change theory proposed here has its roots in psychotherapy. It was developed as a result of dyadic therapeutic relationships. But it is proposed that the same principles are relevant to social change, that the individual change process is but a microcosm of the social change process. Disparate, unintegrated, warring elements present a major threat to society, just as they do to the individual. The compartmentalization of old people, young people, rich people, poor people, black people, white people, academic people, service people, etc., each separated from the others by generational, geographical, or social gaps, is a threat to the survival of mankind. We must find ways of relating these compartmentalized fragments to one another as levels of a participating, integrated system of systems.

The paradoxical social change theory proposed here is based on the strategies developed by Perls in his Gestalt therapy. They are applicable, in the judgment of this author, to community organization, community development and other change processes consistent with the democratic political framework.

When I first attended a Buddhist weekend retreat I was asked to bring with me something which was significant or held meaning for me. It took me a long time to think of anything that fitted this description, but after some reflection I remembered the ‘Litany against Fear’ from Frank Herbert’s novel ‘Dune’, a book that had been very important to me in my teenage years:

Fear is the mind-killer.

Fear is the little death that brings total obliteration.

I will face my fear.

I will allow it to pass over me and through me.

And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path.

Where the fear has gone there will be nothing.

Only I will remain.

The night before I left for the dry Spanish valley where I was to spend four months on my ordination retreat I felt compelled to watch David Lynch’s (notoriously poor) movie of the book (this was before the Sci-Fi Channel’s diligent, but uninspiring mini-series). Then, a few years later, I led a weekend retreat exploring the novel, as a way of looking at the myths and symbols of science fiction and the extent to which they might be useful in terms of spiritual practice.

I have come to deeply value the role of myth and the imagination within my own spiritual practice, but had noticed that a number of my friends found the whole area completely mystifying. It seemed more than a coincidence that many of these people seemed to be fans of science fiction. My aim for the weekend was to help people to make the connection between the myths that they were responding to in sci-fi, and the mythical aspects of life and spiritual practice. It seems that for many people living in a world marked by scientific reductionism and utilitarian literalism, the world of the imagination can appear to be in the future, or ‘A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away.’

Traditionally science fiction has not been a particularly refined genre – in the sci-fi books I read in my teens and twenties, the qualities of writing and of character development were often poor, and violence and cruelty were common themes. It has also been a particularly obvious outlet for wish fulfilment, or for the articulation of contemporary views – the Cold War led to a huge number of ‘alien threat’ novels and movies during the fifties and sixties, and more recently political correctness has brought us the elected Queen Amidala of Star Wars: Episode 1.

At its best, however, the freedom to define new social and political systems, and even change the laws of physics (Captain!), can allow science fiction writers to introduce archetypal figures and explore the nature of the human condition in a way which is not possible in more socially realistic fiction. In this way I believe it is possible for sci-fi to provide a launching pad into the imaginal realm. Thankfully, contemporary writers have begun to marry high standards of writing with this complexity of concepts – although I don’t read much fiction these days I’d particularly recommend Neal Stephenson‘s genre-busting books.

Those who are chronically averse to science fiction are unlikely to become converts, but if you have nurtured a secret affection for sci-fi then perhaps you can begin to have the courage to come out of the galactic closet. Ultimately it may be that science fiction can even be useful in helping us to see how those that we perceive as ‘alien’ are in fact no different from ourselves.

Dune

Frank Herbert, 1965 (published by New English Library)

Set in a feudal society of the far distant future the novel charts its protagonist’s maturation and fourfold initiation: firstly to Duke, then to manhood and leadership, to prescient super-being and ultimately to Emperor. Herbert interweaves his twin interests in psychology and ecology through the symbolic aspects of the story, such as the desert planet Arrakis (the ‘Dune’ of the title) and its giant sandworms, as well as through the themes and characters. These themes include the integration of masculine and feminine, and the principles of prescience and memory. The hero’s teachers are classic Jungian archetypes, and the desert planet is peopled by the wild and fierce Fremen, who live in rock warrens, and hoard water which will one day allow them to catalyse an ecological transformation of the planet. There is also the secretive Bene Gesserit sisterhood who manipulate religions and genetic lines through the use of their greatly heightened powers of awareness.

As a teenager it was this combination of the psychological and ecological which appealed to me, and I was particularly struck by the incredible acuity of perception of the Bene Gesserit – a faculty I now know as mindfulness. In ‘Dune’ Herbert achieved a level of symbolic truth which surpasses anything else he ever wrote, and it is this symbolic content more than the subtlety of his concepts which makes it a great novel.

I was doing some house-keeping on my computer this morning and came across this piece, which I wrote for the Buddhist Arts magazine Urthona about a decade ago – I’ve tweaked it slightly to bring it up to date a bit. I’d love to hear your recommendations for good sci-fi – ancient or modern.

There are many hundreds of meditation practices found in religious traditions and personal development systems throughout the world, and although it might look like people are all doing the same thing when they sit with their eyes closed, they might well be doing any of this huge range of different things. One way to get an overview of all these different approaches, is to see them as fitting into one of four broad categories – or maybe a combination of two or more of them.

There are many hundreds of meditation practices found in religious traditions and personal development systems throughout the world, and although it might look like people are all doing the same thing when they sit with their eyes closed, they might well be doing any of this huge range of different things. One way to get an overview of all these different approaches, is to see them as fitting into one of four broad categories – or maybe a combination of two or more of them.

Concentrating

In this types of practice you focus your attention on one aspect of your experience, and train yourself in regulating your attention by patiently and consistently bringing your mind back to this focus of attention whenever it drifts off. Meditating in this way calms and focuses your mind, and brings together all your scattered energies and thoughts. Body awareness meditations and mindfulness of the breath are both practices of this type, and are this approach is the best way to learn to meditate for most people.

Generating

In these meditation practices, you bring into being, or further develop, a positive quality or state of consciousness, using your imagination, memory and will. The classic example of this type of meditation is the family of meditations known as the Brahma Viharas, which are also called The Four Imeasurable in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. The root of these is the cultivation of loving kindness (metta bhavana or maitri bhavana), the fundamental state of positive regard and well wishing which underlies all others. When you experience metta and you encounter suffering, then your natural response is one of compassion (karuna), and when you encounter growth, development and happiness your response is one of sympathetic joy (mudita). The fourth practice is the cultivation of equanimity – the capacity to respond creatively and from your values without being either overwhelmed by all the suffering in the world, or intoxicated with pleasure.

Receiving

This approach can be seen as complementary to the concentrating practices, because instead of focusing the attention on one specific aspect of your experience, when practising in this way you seek to remain open to all of your experience even-handedly. This type of meditation is often done with your eyes slightly open, so that you pay equal attention to images, sounds, physical sensations, etc. and allow them all to come and go without getting caught up with any one of them. Japanese Zazen and the Tibetan practices of Dzog Chen and Mahamudra can be seen as practices of this type.

Reflecting

Once your mind is settled, then you can turn your focused attention onto your experience so that you can see it more clearly. This might mean observing the way in which your thoughts, feelings and sensations come and go, or exploring your experience to try to identify the self that we all presume to be there. Sometimes, as in koan practice, this might include the use of words, but often it is more an attitude of inquiry, as your mind may be too refined for discursive thought.

Mixing and Balancing

Any particular meditation practice might include any one, or several of these four modes or dimensions of practice, with many complex meditations in the Tibetan traditions including phases of each.

It is worth remembering that these definitions are just a guideline, as the practices do not have distinct boundaries, and whenever you are meditating you need to maintain a balance between consciously guiding your attention (concentrating) and being receptive to whatever experience is arising (receiving). If you focus too much on concentrating your meditation will become tight and dry, but if there isn’t enough focus then you are likely just to drift away from meditation into daydreams.

I have been meditating for nearly 20 years, and the more I meditate the more important awareness of the body seems to be. This isn’t the way I was originally taught to meditate, however this approach to teaching meditation is now the one that is followed by most of the meditation teachers that I know.

We live in a busy world. Most of us live in urban areas and receive huge amounts of stimulus from adverts, people, music, noise, television, ipods, phones – I could fill the rest of the page with this list, so let’s leave it there. When we look at the lifestyles of humans through most of their evolution, we can see that they had much simpler and less stimulating lives. It seems likely that we have not evolved to deal with the high levels of stimulation that we currently receive – no wonder so many of us feel overwhelmed so much of the time.

There has also been a huge change in what we do with our time, with a continual move away from activities that involved our whole bodies towards work that involves only our heads and our hands. Although this process has accelerated during the last century, we’ve been losing touch with our bodies for quite some time.

So what? Well the big problem is that if we lose touch with our bodies, we lose touch with our emotions. They still underlie (and so effectively control) our thinking, but if we can’t feel our feelings we can’t take them into account, make allowances for them, or compensate for them. You only have to observe how venomous and irrational many academic disputes are to see the way that denied emotionality complicates things enormously.

During the period when the founders of the great religions taught there was no need to teach about emotional intelligence – everybody was in touch with their emotions – they just had to teach about which emotions to support and cultivate and which emotions were unhelpful and should have energy withdrawn from them. For many of us, there is a lot of work to do in connecting more honestly with our emotions and feelings, as only then can we begin to transform them. If we don’t, then we run the risk of deluding ourselves, and will struggle to connect effectively with others.

The simplest way to do this is to learn to notice the subtle sensations in our bodies, particularly in the front of the body: the heart, the belly, and the crossroad of nerves between them called the solar plexus. Although we’re all familiar with carrying emotional tension in our shoulders and other muscles, it is in this tender front of our bodies that we can most fully connect with our feelings and emotions.

There’s no need for me to go into the philosophy of this stuff here, but everybody is familiar with Descartes’ famous dictum “I think, therefore I am”. I believe it would be much more helpful for us to be able to say “I think and feel, therefore I am”.

This is another in the series of pieces on emotions that I ghosted a few years ago for a book on The Inner Work of Leadership, which I don’t think was ever published. Rereading this piece I’m reminded how much of the material was simply stuff we all need to address in the process of personal and spiritual development, just with a few phrases inserted to highlight its pertinence for leaders in organisations. I guess that’s why I feel it’s worth publishing here.

Loneliness and Aloneness

We all feel lonely from time-to-time. Humans are social creatures, and we need to have a sense of connection to other people in order to be fully human.

Ironically, the experiences of disconnection and isolation that loneliness engenders have a tendency to distance us from others, so that we send out signals that drive people away at the very time when we most need connection. You will need to develop the ability to reach out to others, both when you are being rebuffed by someone in distress, as well as when you feel lonely yourself.

It is important to be able to distinguish between loneliness and the existential experience of aloneness, because this experience of aloneness is often accentuated for leaders. In your work there will be many problems, challenges and successes that you are not able to share with anyone else in a meaningful way: confidential and business sensitive matters, and things that others will not fully understand.

To lead effectively, you need to be able to step away from those seeking to influence you, as well as to be aware of your extrinsic motivations – your tendencies to look to others for approval and guidance, and to seek recognition and reward. It is unlikely that all of your motivations will be intrinsic to you, and so it is essential that you are aware of these extrinsic motivations so that you can take them into account and take advantage of them, make allowances or compensate for them as appropriate. If you are not able to stand alone in this way your decision-making processes will always be compromised.

It’s true that it can be lonely at the top, and you need to be able to balance your human need for connection with the resourcefulness to make best use of your aloneness.